…seeing that I was good for nothing, of my own free will I became a poet and a rhymester. That is a trade which one can always adopt when one is a vagabond.

–Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris

Victor Hugo (1802-1885) was born in turbulent times. His father, a not always successful officer with Napoleon’s army, also fought frequently with his wife. The combined marital and martial strife meant that Hugo spent his early years almost constantly on the move, with little stability until 1815, when Napoleon fell from power. Hugo converted to his mother’s royalist views—his political opinions would later greatly change on this point—and agreed to study law. His real love, however, was always for poetry. He had a talent: on the strength of his first book of poems alone, Odes et poesies diverses (1822), the restored Bourbon king granted him a pension.

Note: This post is VERY spoilery, since I can’t discuss the book without discussing the ending.

That pension allowed Hugo to indulge a passion for art, history and architecture for a time. Alas for Hugo, that government pension lasted about as long as the restored Bourbon monarchy, which is to say, not long. Louis XVIII died in 1824; his successor, Charles X, was deposed six years later. To earn money, Hugo soon turned to writing prose novels and plays, mostly to great success, combining his skill with prose with his passion for art and architecture in his 1831 novel, Notre-Dame de Paris, better known in English as The Hunchback of Notre Dame, though in this post I’ll be sticking with the French name.

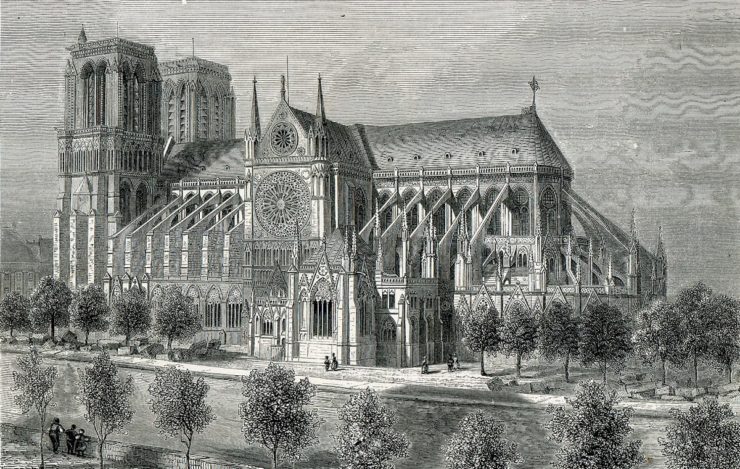

The novel is set in 15th century Paris when—from Hugo’s perspective—Paris architecture was at its height, and when Paris teemed with different cultures and languages. That setting allowed Hugo to include several non-French characters and litter his text with sentences and full conversations in Spanish and Latin. But exploring different ethnic groups was, for Hugo, only a secondary concern. As the opening lines betray, his real interest was in the many historical buildings in France that, after the French Revolution, were falling into decay—when, that is, they were not simply getting razed to the ground. To be more fair to Hugo’s contemporaries than Hugo himself often was, this was hardly a 19th century development. Previous rulers of France had frequently torn down, rebuilt, and redesigned buildings, roads and street plans as French cities expanded beyond their Celtic and Roman roots. But from Hugo’s perspective, this destruction/construction mania seemed to be gaining speed in the first half of the 19th century. He was particularly concerned about Paris’ central cathedral, Notre Dame, a Gothic building damaged during the French Revolution.

Buy the Book

In the Watchful City

This was hardly the first time the cathedral and the artwork had been targeted by outraged Parisian citizens, but previous attacks (for instance, a 1548 Huguenot riot) had been followed up by relatively swift repairs. That did not immediately happen in the years after the French Revolution, a period when most residents of Paris had other, more immediate concerns than a former cathedral turned into a food warehouse. The building still stood, after all, and the bells remained in the tower.

(Later, architects realized that the largest bells actually slightly contributed to Notre Dame’s deterioration: they were loud enough to make the entire building vibrate. But that was years to come.)

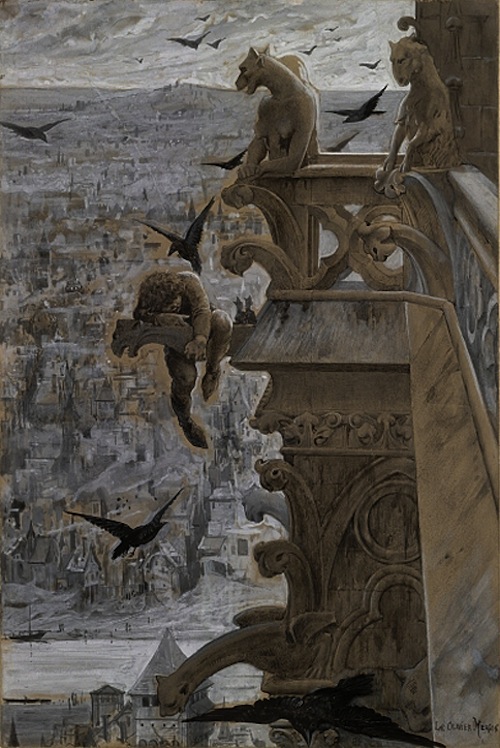

Hugo was not so sanguine. As a firm proponent of the belief that architecture was the supreme expression of human thought (something Notre Dame de Paris spends a full chapter discussing) and that Notre Dame was one of the supreme examples of that expression, Hugo was dismayed by the church’s deteriorating condition, and the possible loss of its artwork and the great towers. He also disliked nearly all of the many alterations to Paris street plans and public buildings, most of which, in his opinion, made Paris less beautiful, not more. His novel would, he hoped, alert readers in Paris and elsewhere to the problems, and possibly—hopefully—save the cathedral.

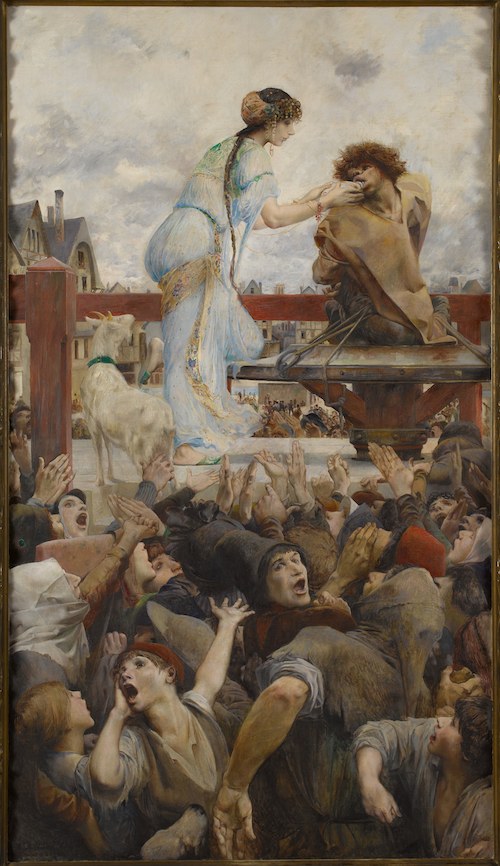

Hugo was savvy enough, however, to know that launching the book with this was perhaps not the best way to lure in readers and convince them that the great cathedral needed to be improved. Instead, he interwove his lectures, rants and despair about Parisian architecture through the pages of his novel, usually at the most exciting points. His great description of Notre Dame, for instance, is carefully placed right after a dramatic moment where a beautiful girl has saved the life of a poet by means of an unexpected and probably not all that legal marriage but then refused to sleep with the guy who ends up comforting himself by playing with her goat (not a euphemism)—the sort of drama that few writers would choose to follow with a lengthy discourse on architecture.

But Hugo also knew that his readers were not about to read these critically important—to him—discourses on architecture without some sort of hook. Thus the book’s general setup: character introductions, a few sad complaints from Hugo’s authorial insert, poet Pierre Gringoire, about the difficulty poets and writers have of getting an audience to pay attention to them (I hear you, oh Victor Hugo, I hear you), street fights, failed romance, and then CHURCH ARCHITECTURE, followed by melodrama, more street fights, ARCHITECTURE, a few borderline kinky bits that certainly help to explain the book’s popular success, ARCHITECTURE, rains of fire, betrayal, VERY HIGH DEATH COUNTS, ARCHITECTURE, mean things about kings, and then ARCHITECTURE and DEATH. At one point, even Hugo confesses himself a bit overwhelmed by all the architecture and his own melodrama, admitting:

Here we are unequal to the task of depicting the scene.

This does have the negative effect of making all of the ARCHITECTURE bits feel somewhat equivalent to the moments in Les Miserables when Cosette starts to sing. But only somewhat, since quite a lot of what Hugo has to say about Notre Dame, and what people—specifically kings, revolutionaries, artists, everyone in Paris, architects, and humanity in general—have done to Notre Dame, is if not quite as compelling as the rest of the book, definitely worth reading, filled with various fascinating tidbits of history, prisons, reflections on the meaning of art, the impact of the printing press, and everything that had, for Hugo, gone wrong with Paris construction in recent years, all laced with the cynicism that pervades the novel, whether Hugo is discussing architecture, or poets, or church leaders, or kings, or anything, really, other than goats.

Still, the real draw of the novel turns out to be not the passionate discussions of architecture that inspired it, but the characters, few likable (except the goat) but all memorable (especially the goat.) They include:

- Paquette de Chantefleurie, convinced that gypsies have eaten her child. She has ISSUES as a result.

- Jehan Frollo, supposed to be studying and doing well in the world, who instead spends his time wishing that the courtesans he hires would spurt wine from their breasts (he really says this) because he has not learned much about anything, much less biology.

- In a cameo appearance, cheapskate, paranoid king Louis XI, who wants criminals hanged because of the appalling costs of keeping them in prison, and who also has huge issues with the colors of sealing wax his fellow kings use, and only agrees to step in to stop an angry mob which is already harming buildings and people when he thinks it might be after him.

- Amazingly good looking Phoebus, the sort of guy who tears beautiful gypsy girls from the arms of dazed hunchbacks and throws them (the girls) across his saddle, and then cheerfully agrees to let seriously creepy priests watch him have sex with said girls for the first time (this would be one of the borderline kinky bits) without telling the girl they are being watched, like, Phoebus, I’m all for exhibitionism if it’s your thing, but let the girl in on it, thanks.

- Fleur de Lys, the sort of person who marries a guy like that largely because he’s hot and, well, why not.

- Esmeralda, the lovely dancer, called “gypsy” or “Egyptian,” who earns the love of an adorable goat and some rather less adorable men, and who, I’m sorry to say, when about to be killed by an evil priest announces that she loves Phoebus because he’s better looking than the priest, which is true, but not exactly the most tactful or intelligent thing to say at this point.

- Various officials completely unconcerned about the exhibitionism/voyeurism scene mentioned above, and more concerned about the rather suspicious circumstances that immediately follow it: blood, a knife at a soldier’s neck, a man dressed in black, a black mass, the goat, and a coin “mysteriously” replaced by a leaf.

- Multiple gossipers, torturers, angsty government officials, some Flemish ambassadors, a completely deaf judge, and irritated students.

- Garrulous, talkative poet Pierre Gringoire, very loosely based on the real life 16th century poet and dramatist Pierre Gringoire, more or less the main character, but mostly used by Hugo as his mouthpiece to complain about the writing life and how no one understood what he was saying but they certainly would if he could just get them to listen, the tragic reality that herders are better off than poets, since herders don’t have to worry that political marriages between kings and duchesses of Burgundy will lead to a ruined theatrical performance and the complete end of a poetic career. Some things about writers don’t seem to have changed much since 1831. Hugo also used Gringoire to complain about other things that bothered him, like how confusing Paris streets are (now imagine navigating them with a group of drunk Canadian tourists, Hugo), little ragged kids who threw stones at him just because he was wearing nice pants, and priests who created faked miracle stories about straw mattresses. The sorts of things that bug us all.

And, stealing the show, three characters who don’t even appear in the first several pages:

- Claude Frollo, Archdeacon of Notre Dame, alchemist and voyeur and completely terrible brother, who is shocked, shocked to find that framing a woman for the murder of the man she’s in love with is not the best way to win her heart.

- Quasimodo, the evil, deaf, redheaded hunchback with only one eye.

- A goat, trained to do goat tricks that are not exactly kind to the political establishment.

Frollo is more or less the novel’s antagonist—more or less, because few of the characters in this book can be called sympathetic, much less good, and several other minor characters work to impede and harass the major characters. And Frollo is hardly the only character responsible for the high death count at the end of the novel. But he’s arguably the most—well, I don’t want to say compelling, but creepy, in a book that includes people who enjoy torture.

Claude Frollo has two goals in life: ruin everyone’s fun, and sleep with Esmeralda. She, understandably, is less than enthusiastic about this, not so much because Frollo is a priest, but because Frollo is a creepy priest, going to the point of paying Phoebus money to watch him—Phoebus—sleep with Esmeralda. He also turns out to be a gaslighter beyond compare, blaming Esmeralda for making his life miserable—this, right after he framed the girl for murder, leading directly to her torture and imprisonment. Also he’s kinda racist, if not much more so than everyone else in the book. At least he’s not accusing the city’s gypsies and Africans of cannibalism, unlike others in the book, which I guess is something.

About the only good deed I can credit him for—well, I suppose, apart from sorta taking care of his mostly useless brother—is saving the life of Quasimodo, an ugly, deformed child left in the place of a lovely baby girl, in Hugo’s general nod to fairy tales as well as an exposure of the horror behind some of those tales. With Frollo’s help, Quasimodo not only lives, but gets a job as a bell ringer in Notre Dame. In many ways, this is excellent for him: as a half blind, poorly educated, not overly intelligent man with multiple physical issues, his opportunities are limited, and bell ringing at least gives him a job and a purpose. But, as with so many kindly meant gestures (a point Hugo makes over and over again in this book) it ends up making things worse: the bells take away Quasimodo’s hearing.

This does lead to a great scene later where a deaf judge questions the equally deaf Quasimodo, leaving them both of them completely unaware about what’s going on, one of Hugo’s many unkind depictions of the French legal system, but since Quasimodo isn’t reading the book or particularly interested in critiquing the French legal system, this benefit is lost on him. It also leads to a very important plot point towards the end of the book, which results in A NUMBER OF UNNAMED PEOPLE GETTING BURNED ALIVE and THE DEATH OF JUST ABOUT EVERYONE ELSE LIKE THANKS AGAIN, FROLLO, YOU JERK, FOR DOING ALL THIS TO QUASIMODO. But the deafness also helps isolate Quasimodo still further.

Not surprisingly, Quasimodo becomes malicious. Hugo claims that Quasimodo was malicious because he was savage, and savage because he was ugly—a progression which can be a bit troubling to read, especially for readers with disabilities, but I would argue that there’s more going on here: Quasimodo is also malicious because, with the exception of one person, the world has been really malicious to him. His parents abandon him shortly after his birth (stealing a baby to replace him); most of the people who see him after that want him dead; and the one thing he can do ends up making him deaf. He has exactly one happy moment in the book: when he’s picked up, dressed up, and turned into the Pope of the Fools—someone to be mocked. This would be enough to turn most people bitter, and this is before including having only one eye and the various other physical issues. As Hugo also adds, “He had caught the general malevolence. He had picked up the weapon with which he had been wounded.”

Quasimodo is hardly the only character judged, fairly or unfairly, by appearances: that also happens with Fleur de Lys (positively, since she’s beautiful) and Phoebus (ditto), and Esmeralda (not so much). Which leads to some questionable assumptions, such as Fleur must be sweet (er), Phoebus must be good (er), and Esmeralda must be a gypsy. Or Egyptian. After all, just look at her. Not to mention what she’s wearing. And the people she is hanging out with. As such, Esmeralda is seen as exotic, different, other. Even if, as Hugo casually notes, many of the people perceived as “gypsies” are no such thing, but rather German, Spanish, Jewish, Italian or any other of a number of different nationalities.

That clue casually planted, Hugo waits until the final chapters to drop his bombshell: Esmeralda, until that point assumed by everyone (including herself) to be absolutely, positively, not French, turns out to be, well, born—if not exactly in holy wedlock—to very French parents.

That is, French.

Meanwhile, every character also assumes that Quasimodo is absolutely, positively French (well, more specifically, a demon, but still, a French one, which makes him the better sort of demon).

He’s not.

It’s a scene so over the top that, temporarily, even Victor Hugo is overwhelmed by his own melodrama, and readers can be forgiven for getting so caught up in the melodrama that they miss Hugo’s main point here. Fortunately, Hugo and readers have another character to keep them from spiraling too far into melodrama:

The goat.

I know what you’re thinking. But trust me, this goat is AMAZING: the hands down nicest, friendliest, and most sympathetic character in the entire book. Granted, Hugo’s general cynicism about humanity, dripping from every page, means that’s not really a high bar, but still: this goat? Adorable. It does tricks. It counts numbers. It spells things. It comforts Esmeralda and Gringoire when they are feeling sad. It’s loyal.

Alas, I am very sorry to have to note that not everyone appreciates the goat. SOME characters even choose to charge the goat with a crime:

“If the gentlemen please, we will proceed to the examination of the goat.” He was, in fact, the second criminal. Nothing more simple in those days than a suit of sorcery instituted against an animal.

Unfortunately, because the goat has no sense of self-preservation, it responds to this accusation by doing little goat tricks, which convince everyone that the goat is actually the devil and thus has to be hanged.

GASP.

Fortunately for the goat, one person, Pierre Gringoire, recognizes the goat’s true qualities. When faced with the terrible choice of saving Esmeralda, the beautiful girl who refuses to sleep with him, or the goat, who regularly head butts him, Gringoire wisely—in my opinion—chooses the goat.

I cheered.

It must be admitted that despite this unexpectedly wise note, most readers find that Notre-Dame de Paris has an unhappy ending, largely because many of the characters end up dying gruesome deaths, and even those that don’t face grim fates such as this:

“Phoebus de Chateaupers also came to a tragic end. He married.”

But, given that I spent most of the book kinda hoping that most of the characters would die, and feeling rather gleeful when they did, I can’t entirely agree that the ending is unhappy. I mean, come on—they saved the goat.

For a 19th century novel filled with characters voicing racist opinions, and whose kindest, most sympathetic character is a goat, Notre Dame de Paris is not just an extraordinary read, but also remarkably progressive. Not just in its examination of racism and shifting culture identities, but also justifications for torture (Hugo is unimpressed), the male and female gaze, ethnic integration, justice, gender roles, and identity. Also architecture.

Possibly because of that progressivism, or because of the goat, or just possibly because it really is one hell of a novel, Notre-Dame de Paris was an enormous success. Its popularity helped get Hugo elected to the French Academy in 1841. Two years later, however, grief stricken by the tragically early deaths of his daughter and her husband, Hugo stepped back from writing and publishing. In 1845, still unable to write, he watched Gothic Revival architect Eugene Viollet-le-Duc start the restoration of Notre Dame.

Hugo fled France in in 1851 for political reasons, eventually spending fifteen years on the isle of Guernsey. The hardships of his exile were possibly mollified by the beauty of the island, which he fell in love with, the lovely house he was able to purchase thanks to his publishing success, and the arrival of his mistress, Juliette Drouet. There, Hugo finished his other great masterpiece, Les Miserables, a novel which would eventually lead to crowds of people singing “Do You Hear the People Sing” in various locations, appropriate and not. He eventually returned to his beloved Paris, dying there in 1885.

In recognition of his poetry and other works, he received a national funeral. After lying in state beneath the Arc de Triomphe, he was buried in the Pantheon, honored as one of the greatest citizens of France.

A little more than a century later, Disney thought it might be a nice idea to honor him by adapting his novel into an animated film.

Originally published in February 2016 as part of a series comparing Disney’s animated films to their source material.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

Victor Hugo is also a saint- in the Cao Dai religion.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caodaism

This is awesome. I had more and better expectations of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, but at least it seems to be very funny. I laughed out loud , for example at the line about the guy who met a tragic end by marrying.

I would argue the ethnicity stuff is not progressive at all. So the pretty girl turns out to be French and the disabled, repeatedly described as ugly kid is Romani, and this is all because the Romani characters literally kidnapped the pretty baby. Which is a myth that has had horrible effects in Europe for ages. In The Man Who Laughs, Hugo claims that the Romani can’t legitimately claim to be persecuted, unlike the Sephardim and Huguenots, because we can’t “confound a persecution with a battue” aka hunting of animals. Hugo was progressive on many issues like abolition of the death penalty, but not on this.